Mezzotint: Painting with Darkness

Where Seven Streams Fall mezzotint by Stuart Brocklehurst

Introduction

Mezzotint, from the Italian mezza tinta meaning half tone, is one of the most atmospheric and distinctive printmaking methods in the history of intaglio. Known for its seamless tonal transitions, deep velvety blacks, and painterly softness, the method once dominated eighteenth-century print reproduction, particularly portraiture, before the arrival of photography.

Elizabeth E. Barker summarises the essence of the technique beautifully:

“A mezzotint emerges out of the darkness into the light.” (The Printed Image in the West: Mezzotint)

Siren Song, mezzotint by Janet Cox

The Technique: Working from Darkness to Light

Unlike engraving or etching, mezzotint is a drypoint tonal method. It does not depend on lines or chemical etching, but instead uses the physical surface texture of a copper (or steel) plate to create tone.

Stage One: Preparing the Ground

The artist uses a serrated tool known as a rocker or cradle, which is rocked repeatedly and methodically across the plate. This action raises thousands of tiny burrs and pits that act as reservoirs for ink.

If printed at this point, the plate would produce a field of pure, velvety black. An earlier variation of this process used a roulette, a small toothed wheel that punctured the surface. Today, some artists also roughen plates using carborundum stone.

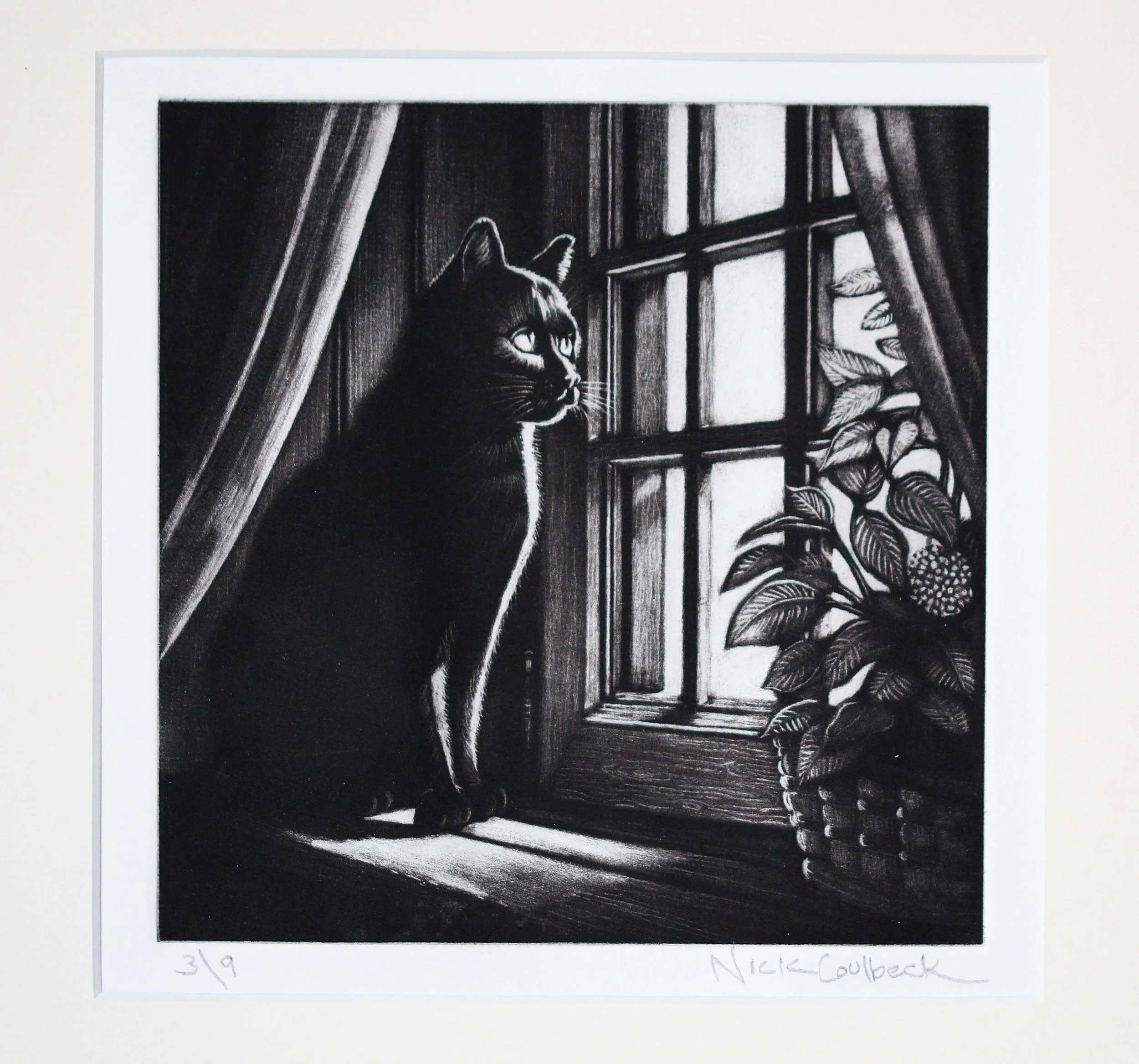

What can I see, mezzotint by Nick Coulbeck

Stage Two: Creating the Image

With the dark base established, the artist then begins the act of removing darkness using: a scraper, a burnisher and sometimes supplementary engraving tools. The burr is gradually smoothed and polished. The smoother an area becomes, the less ink it holds, producing transitions from deep shadow, through mid-tone, to the brightest highlights. William Hogarth captured this reversal of traditional artistic logic in 1753:

“The copper-plate … is first wrought to print one even black, like night: and the whole work afterwards is merely introducing the lights into it.” (The Analysis of Beauty).

In French, mezzotint is known as la manière noire — the dark manner — a reference not only to process but to aesthetic character.

Tools and Materials

Traditional mezzotint requires only a few essential tools and materials: copper or steel plate, rocker or roulette, scraper and burnisher, ink and an intaglio press.

Because the burr is delicate and flattens over repeated printing, a mezzotint plate typically yields a relatively small number of high-quality impressions. Early prints are the richest and most highly valued.

A Sustainable Printmaking Method

Modern practitioners value mezzotint not only for its tonal richness, but also for its environmental benefits. Printmaker Martin Maywood of The Ropewalk, Barton-Upon-Humber, notes:

“Using no chemicals, mezzotint engraving is a very green and environmentally friendly method of intaglio printmaking with the ability to render images in photographic detail with a full range of velvet tones.”

Contemporary Practice

Although labour-intensive, mezzotint remains an admired and relevant method. Artists today continue to refine the process and expand its expressive vocabulary. At Eastgate Studio, the work of Janet Cox, known for her gothic sensibilities and mastery of form and tone, is especially celebrated.

Why Mezzotint Endures

Mezzotint remains one of the most expressive forms of intaglio printmaking. It offers: atmospheric depth, silken tonal gradation, a painterly quality unmatched by other printing methods. Its slow rhythm and physical craft encourage contemplation and technical discipline. Though no longer used for rapid reproduction, mezzotint holds a unique place in printmaking: a technique where shadow is shaped by hand, and the image appears gradually, like light emerging through mist.

Further Reading and Credits

Elizabeth E. Barker — The Printed Image in the West: Mezzotint

William Hogarth — The Analysis of Beauty (1753)